Pom and Circumstance

2 synagogues, a Jewish Surinamese Casserole, and the Fragility of Memory

A Diaspora Dinners essay | by Elli Benaiah

At first, I thought this would be an exotic but rather marginal topic. But as I delved deeper into my research discoveries, I became so absorbed that the essay spilled over. For this, I apologize—yet I hope you find it as engagingly layered as I do.

Far from a promised land — and not on a Caribbean holiday — that is how Jews came to Suriname.

Suriname, the smallest country in South America, is today a nature lover’s paradise: over 90% of its land is dense rainforest, with rivers teeming with rare flora and fauna.

Its population is a mosaic of peoples — Indians, Javanese (from the island of Java), Maroons, Creoles, Indigenous Amerindians, Chinese, and Europeans. The Maroons (from the Spanish cimarrón = “wild, untamed”) were communities of formerly enslaved Africans who escaped Dutch plantations in the 17th and 18th centuries, building independent societies deep in the rainforest.

To modern readers, Suriname may seem like a remote and forgotten corner of South America. But in the seventeenth century it stood at the crossroads of a much larger Jewish story in the Americas. From the moment Columbus crossed the Atlantic — and some recent research suggests he may have been of Jewish converso descent — the New World became a fragile but real horizon of possibility for Jews expelled, persecuted, or forced into silence.

Suriname was one such refuge, and a new beginning.

In 1639, Sephardic Jews fleeing the Spanish and Portuguese Inquisition passed through Brazil and the Caribbean before settling in the Dutch colony. Both British and Dutch authorities granted them unusual freedoms: the right to own land, and to worship openly.

They built communities with evocative names — Torarica, the Jewish Savannah (Jodensavanne), and Jerusalem on the River.

They built synagogues, preserved archives, and celebrated Shabbat beneath the rainforest canopy. Their survival in this diaspora showed that Jewish life could take root almost anywhere — even in the tropical soil of the Amazon basin.

A Sephardi Savannah

No story of Surinamese Jewry is complete without Beracha ve Shalom, the synagogue of Jodensavanne, inaugurated in 1685. Built by descendants of the Iberian exiles, its sand-covered floors echoed with Portuguese and Hebrew prayers while its congregants ran plantations along the Suriname River.

Jews became so influential that Sranan Tongo, Suriname’s creole language, absorbed words from Hebrew and Ladino. For example, treif came to mean “bad food.” I would argue with that, but I digress…).

Unlike the Ashkenazi Jews who arrived later, and who leaned toward commerce, Suriname’s Sephardim were unusually tied to plantation agriculture. Still, the distinction was not absolute: Ashkenazim also farmed, and Sephardim traded. But their balance of livelihood gave Surinamese Jewry a unique social fabric.

Hybridity and Scarcity

This fabric was also defined by scarcity. As historian Aviva Ben-Ur - author of Jewish Autonomy in a Slave Society: Suriname in the Atlantic World, 1651–1825 - shows, the limited number of white Jewish women in the colony meant that men often formed families with enslaved or free women of African descent.

At first, children of Jewish fathers and African mothers were raised Jewish, often through conversion. By the early 1800s, there were enough Jewish mothers of colour that descent could follow the maternal line again.

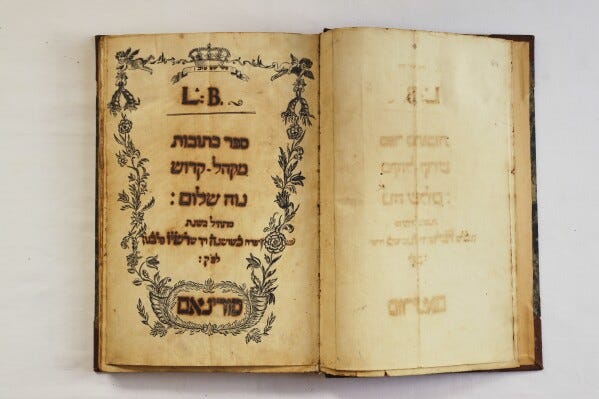

Wedding registers of the Dutch Portuguese Israelite Congregation dated 1766, photographed in Paramaribo, Suriname, Wednesday, April 30, 2025. (Neveh Shalom Synagogue via AP)

Ben-Ur concludes that perhaps the majority of Suriname’s Jews by that time were of African maternal origin.

a Jewish Surinamese family, 1800s

Yet full equality was elusive. A system of jahid (full-rights Jews) and congreganten (second-class Jews) kept Jews of colour in the back benches of the synagogue. By the 1790s, frustrated by exclusion, Jews of colour created their own prayer house.

By the early 1800s, conversions and intermarriage meant that Jews of African descent likely formed the majority of the community — a reminder that hybridity was not only cultural but demographic. Over time, the community itself transformed, shaped by African descent and Creole culture until it became something new.

Resistance forced change, and slowly distinctions were abolished — but the mark of hybridity remained central to Jewish life in Suriname.

Unlike most Jewish communities in the Americas, the Sephardim of Suriname enjoyed extraordinary autonomy: Jodensavanne functioned almost as a “state within a state,” with its own regents, militia, and even judicial authority.

For a time, the synagogue flourished as a center of Jewish life in the New World. But by the late 18th century, it declined under the weight of economic hardship, conflict, and uprisings among enslaved and Maroon communities. Maroon resistance shaped the decline of Jodensavanne and thus indirectly helped spread Jewish life into Paramaribo.

Both Suriname and Barbados remind us that Jewish life in the Americas was never simply “merchant Jews” or “planter Jews,” Ashkenazi or Sephardi, black or white. It was all of these at once: fragile, entangled, resilient. And sometimes, as with pom in Suriname or Bajan curry in Barbados, it was crystallized in food — a dish that tells the truth of who was gathered at the table.

Today, only ruins remain of Beracha ve Shalom — brick foundations, toppled walls, and a cemetery overtaken by tropical growth — yet the site still speaks. It reminds us that Jewish life in Suriname was not a passing footnote but a rooted presence, where exiles carried their rituals and recipes from Spain and Amsterdam to the edge of the jungle.

Pom is part of that inheritance — a Sephardi Jewish casserole re-rooted in Suriname’s soil, absorbed into the national table, and carried forward not just as a Jewish dish but as now a fully Surinamese one.

silent remnants of Jodensavanne

Persecution and Migration - The Ashkenazi experience

By the late 18th century, Jewish life had moved to Paramaribo, the capital. There, the community absorbed both Ashkenazi migration and refugees from Europe. On Christmas Eve 1942, more than a hundred Dutch Jews fleeing the Holocaust arrived to the sound of the Dutch national anthem — a moment of relief and belonging still preserved in the archives.

Dutch historian Rosa de Jong has reconstructed the refugee journey and exile, showing how survival in Suriname came with paradox: safety from Nazi terror, yet also confinement behind barbed wire, colonial restrictions, and tensions both within the Jewish community and with local society. Her research recovers a fragile chapter in Jewish memory, reminding us that Suriname was not just a footnote to the Holocaust but an unexpected stage where exile, adaptation, and identity collided.

Yet even as refugees were welcomed, Suriname lost nearly a fifth of its own Jewish population during the Holocaust. Then a Dutch colony known as Dutch Guiana, Suriname had no universities of its own, so young people often traveled to the Netherlands for education or career opportunities. Many were caught there when the Nazis occupied the country — and became trapped in the machinery of genocide.

“Aunts, uncles, cousins — they were picked up by the Nazis, and after the war they didn’t come back,” recalled Evelyn Stroobach, whose grandmother, Rebecca Fernandes, survived the war in hiding. “There were several Fernandeses killed at Auschwitz. They may have been relatives.”

Jacob Steinberg, Jewish and Surinamese, who was instrumental in raising the funds for the monument at the Paramaribo Holocaust memorial.

Two Synagogues, One Community

In Paramaribo, Neveh Shalom today serves as a Reform congregation. The site was first acquired by the Sephardi Jews in 1716, with the original synagogue completed in 1723. Its present Neoclassical structure, designed by architect J.F. Halfhide, was inaugurated in 1842.

Inside, a small museum recounts the history of Suriname’s Jewish community. Just next door stands the Keizerstraat Mosque — together forming a striking symbol of coexistence at the heart of the city.

The Neve Shalom Ashkenazi synagogue next to the Keizerstraat Mosque , paramaribo, April 30, 2025 (AP Photo)

The Neve Shalom synagogue, Paramaribo, a look inside

By 1735, Neveh Shalom had been sold to the Ashkenazim, prompting the Sephardim to build their own synagogue, Tzedek ve Shalom, the following year.

The Tzedek ve-Shalom Sephardic synagogoue, Paramarimbo, Suriname

The small Jewish community gradually consolidated in Paramaribo, where Neveh Shalom (Ashkenazi, 1735, later shared) and Tzedek ve Shalom (Sephardic, 1736) became the twin centres of Jewish life.

In the 1990s, the two congregations merged, alternating services between the two synagogues and rites. Today, fewer than 200 Jews remain in Suriname, about half formally affiliated, yet their cultural imprint continues to resonate across the country.

Archives Under Threat

In April of this year, a fire swept through Paramaribo’s historic centre, endangering the city’s Dutch colonial wooden buildings — part of a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Just a few blocks away stood the Neveh Shalom Synagogue, guardian of one of the most remarkable Jewish archives in the Americas. Though the flames were contained, the blaze was a stark reminder of the fragility of cultural memory. Inside, another struggle was already underway: against time, humidity, and insects. Volunteers and scholars joined forces to digitize more than 100,000 historic documents — from birth records and land deeds to correspondence and every edition of Teroenga, the community’s congregational magazine.

Ronny Reeder, left, and Rosa de Jong scan images in Paramaribo, Suriname, Friday, May 2, 2025. (AP Photo)

The project was spearheaded by Dr. Rosa de Jong, a Dutch scholar whose doctoral research traced Jewish refugees who fled to Suriname, Curaçao, and Jamaica during World War II. Having combed the archives for her own studies, she returned determined to save them — raising money herself for cameras, hard drives, and travel. “I felt that my work comes with an obligation to preserve the past that I’m building my career on,” she said, invoking her own Jewish heritage.

Those fragile pages chart how Suriname became a hub of Jewish life in the Americas. For decades, community member Lilly Duijm kept them safe in metal filing cabinets. Now, thanks to digitization, more than 600 gigabytes of Surinamese Jewish history are preserved — proof that even on the far edge of the Caribbean, far from the Promised Land, Jewish memory endures.

Rosa de Jong, left, and Lilly Duijm pose in front of the boxes of documents from the archive in Paramaribo, Suriname, Friday, May 2, 2025. (AP Photo)

That past is layered.

Suriname was once a hub of Jewish life in the Americas: Jews managed plantations, built synagogues, and nurtured one of the hemisphere’s most enduring communities.

Suriname’s Jewish story does not stand alone. Across the Caribbean, the Sephardi diaspora left its mark in places like Curaçao and Barbados, where Jews carried both ritual and sugarcraft into plantation societies. In Barbados, as I wrote in my essay Candle in the Dark, descendants like Gavi still keep Jewish memory alive with black Shabbat candles, even as institutions struggle to recognize them. Her family’s story echoes Suriname’s: hybridity born of scarcity and survival, belonging complicated by race and paper lineage, Jewishness lived out in kitchens and living rooms rather than on synagogue rolls.

Both Suriname and Barbados remind us that Jewish life in the Americas was never simply “merchant Jews” or “planter Jews,” Ashkenazi or Sephardi, black or white. It was all of these at once: fragile, entangled, resilient. And sometimes, as with pom in Suriname or Bajan curry in Barbados, it was crystallized in food — a dish that tells the truth of who was gathered at the table.

The Many Flavours of Suriname

Suriname’s cuisine is among the most diverse in the world — a reflection of its layered history and the many peoples who made it home. Indians, Africans, Creoles, Javanese, Chinese, Dutch, British, French, Jews, Portuguese, and Amerindians all left their mark, shaping a food culture where influences mix freely.

Staples like rice, cassava, and tayer (pomtajer, a variety of taro) anchor the kitchen, while chicken appears in countless forms — from Chinese snesi foroe to Indian chicken curry, and, most famously, pom, the beloved Creole casserole served at celebrations.

Salted meats, stockfish (bakkeljauw), and vegetables such as okra, eggplant, and yardlong beans round out the pantry, always brightened by the fiery Madame Jeanette pepper.

Beyond pom, roti is another festive favorite, filled with curried chicken, potatoes, and vegetables. Other classics include moksi-alesi (a one-pot rice dish with salted meat, shrimp, or fish), peanut soup, fried plantains, and Javanese-inspired nasi goreng and mie goreng.

Desserts range from boyo (a sweet coconut–cassava cake) to fiadu (a fruit and nut cake) and maizena koek (delicate cornstarch cookies scented with vanilla).

Surinamese food is, in short, a cuisine of connections — each dish a story of migration, adaptation, and celebration.

A marketwoman in Paramaribo

From a Spanish Sabbath Table to Surinamese Identity

So Pom is no ordinary casserole. To the uninitiated, it looks rustic: chicken baked beneath a crust of grated pomtajer root, seasoned with citrus, spices, and sometimes tomato. But beneath its surface lies a history of migration and adaptation.

Widely considered Suriname’s national dish, pom is served at weddings, holidays, and festive gatherings. Yet its origins trace back to the Sephardi Jewish community.

As written archives face fire, decay, and insects, pom has become the edible archive of Surinamese Jewish memory — preserved not on paper but in kitchens.

Food as Archive

Visiting Assistant Professor Eli Rosenblatt calls Surinamese Jewry “Creole Israel” — a community formed at the intersection of Europe, Africa, and the Caribbean. Festivals like Purim absorbed African elements; prayers mixed with plantation realities. Pom is the edible reflection of this hybridity.

Born from the Sephardi Sabbath casserole tradition (hameen, cholent), it replaced Old World potatoes with pomtajer (Xanthosoma), a starchy root of West African origin. The dish layered chicken, citrus juice, and spices with grated root in a casserole that could be baked for Shabbat. In time, pom leapt from Jewish homes into the wider Surinamese kitchen. Today it is considered Suriname’s national dish — Jewish in origin, yet embraced by all.

In 17th-century Suriname, potatoes were not yet grown in tropical colonies. Instead, Jews turned to pomtajer. Layered with chicken, citrus juice, and spices, it was slow-baked into a fragrant casserole that fit the rhythm of Jewish ritual while embracing the New World’s ingredients.

For centuries, Jewish and Creole cooks alike used pomtajer as a substitute for the potato — which, ironically, Jews had already encountered in Europe even as much of the continent dismissed it as animal fodder or peasant fare.

The very name pom reflects this layered history. Some trace it to the French pomme (apple), by extension pomme de terre (potato), though the dish contains no potatoes at all. In 17th-century Europe, the potato carried suspicion; in Suriname, pomtajer earned the nickname “Portuguese potato.”

Only later did the potato gain prestige in Europe, thanks to figures like Antoine-Augustin Parmentier, the French agronomist who tirelessly promoted it as a staple crop. Sephardi Jews, however, connected through Iberian and Caribbean trade, had tasted potatoes long before they became fashionable on the continent.

In Suriname, though, they improvised with what grew. Over time, the casserole made with pomtajer became simply pom — a dish whose name pointed nostalgically back to Europe, yet whose substance was rooted in the Americas.

From the Jewish Sabbath table, pom spread to kitchens of every background — Creole, Indian, Javanese, and Maroon. What began as a Jewish adaptation became a national treasure.

In this sense, pom is culinary circumstance made edible: a dish born of necessity, transformed by migration, and embraced as a symbol of Surinamese identity.

Recipe: Pom (Surinamese Jewish Casserole)

Adapted from community recipes, Paramaribo archives, and modern Surinamese kitchens

Serves 8–10

Ingredients

2 kg pomtajer

If pomtajer isn’t available, taro or malanga can be substituted — though purists will insist it changes the character of the dish

1 kg chicken thighs and drumsticks

2 onions, finely chopped

4 cloves garlic, minced

3 tomatoes, chopped

Juice of 3 oranges

Juice of 2 limes

3 tbsp tomato paste

2 tbsp oil (plus more for greasing)

1 tsp ground nutmeg

1 tsp ground allspice

1 tsp ground black pepper

1 tsp salt (more to taste)

1 tbsp brown sugar

1 chili (optional, for heat)

Fresh parsley or celery leaves, for garnish

Method

Prepare the filling: Sauté onions and garlic until golden. Add tomatoes, tomato paste, sugar, and spices. Cook until thickened. Add chicken, simmer 10 minutes, then remove from heat.

Prepare the crust: Grate pomtajer. Squeeze out excess liquid. Mix with orange and lime juice, salt, pepper, and a drizzle of oil.

Assemble: Grease a baking dish. Spread half the pomtajer as a base. Layer chicken and sauce. Cover with the remaining pomtajer. Smooth the top.

Bake: At 180°C (350°F), bake uncovered for 90 minutes until golden and crusty.

Serve: Let rest before cutting. Garnish with parsley or celery leaves. Serve warm.

A freshly baked pom casserole – shredded baked chicken layered with pomtajer and orange/lemon citrus – golden brown after slow baking. This iconic Surinamese dish originated from Jewish settlers adapting their Sabbath stew to New World ingredients.

What Survives

Today, only ruins remain of Jodensavanne — brick foundations, toppled walls, a cemetery overtaken by tropical growth. Yet pom survives, passed from Jewish hands into every Surinamese household. It is not simply the “last survivor” of a vanished community, but rather the marker of a community transformed — a people remade through mixture, adaptation, and endurance.

Historian Aviva Ben-Ur reminds us that Jewish life in Suriname was marked by hybridity — with communities of mixed descent that by the early 1800s may even have formed the majority of the Jewish population. Festivals like Purim absorbed African elements, and Surinamese Jewry enjoyed unusual cultural autonomy.

That same hybridity is baked into pom: a Sephardi Sabbath casserole re-rooted in the tropics, then absorbed into the national cuisine.

In this sense, the community did not vanish but morphed into the fabric of Suriname itself. As Rosa de Jong and her colleagues race to digitize brittle archives, pom endures as a living archive you can eat — a reminder that memory sometimes survives not in a synagogue or a ledger, but in a casserole shared at the family table.

Call to Action

👉 Have you made pom? Do you carry family recipes where food keeps memory alive? Share your story in the comments or pass along this essay. And if you’d like to support more work uncovering Jewish food in unexpected corners of the world, subscribe to Beyond Babylon.

With gratitude to Rosa de Jong for her invaluable help in widening my understanding of Surinamese Jewish history, allowing me to write a better recipe — and, I hope, a truer story.

You are such a master storyteller, Elli! I've always loved history, and the way you chronicle events shows your exceptional skills at this art! Adding a good recipe with such a rich historical background rooted in the country's multicultural past makes it even better! 😊

When I was younger, half a decade younger, in an attempt to contextualize my own existence, as a Creole Jew, a Creole-Sephardim, I turned to Suriname to see how they had fashioned, spoke of themselves and even came to be. I found tremendous similarities, and even turns I would adopt for myself, more modern terms than what my mother would use, like "Mulatto", instead "Eurafrican" "Creole".

At the time I was most ignorant of my country's History - The Spanish Portuguese Nation of Hebrews of The Caribbean, a peoplehood, beyond borders, beyond Barbados, beyond Suriname, but across the entire Caribbean. But I came to learn why I had been ignorant, I came to learn the only information to be found of us were locked behind academic discourse at the highest levels, while descendants did not truly know the depth of what others had said of themselves.

I felt envy, The Spanish-Portugese Surinamese were always more racially... Accepting than the Mahamad of the Barbadian Spanish-Portuguese, they had their struggles, but they formed a community which stood the testament of time, today, it is still around. My forefathers, the actions they took to be complicit in colonialism created my very inheritance today. Fragmented, effaced, obscured, and above all? Erased. Sometimes I wish I was born in Suriname- But articles such as this bring me a little closer to understanding our Kinship as the Spanish-Portuguese, and even more, Jews of the Caribbean and Latin America. For that, thank you, Mr. Alley!

What separates us in geography, can never separate us in spirit, heart, and heritage.

Viva a Nação!